Doctoral Research Poster Showcase

This is a full text description of the poster I presented at the Doctoral Research Poster Showcase. This is intended to be a very general introduction for non practitioners. Experts can go directly to my latest conference proceedings.

Introduction

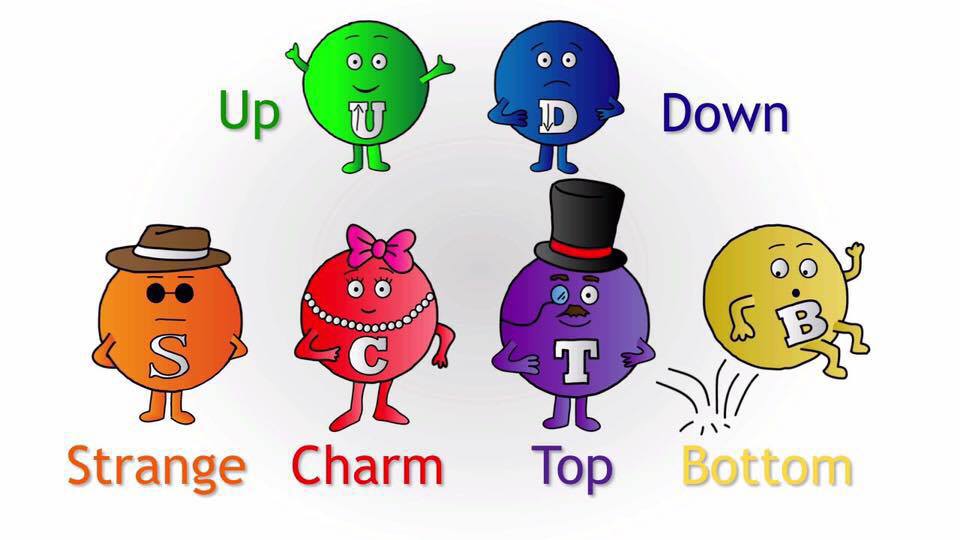

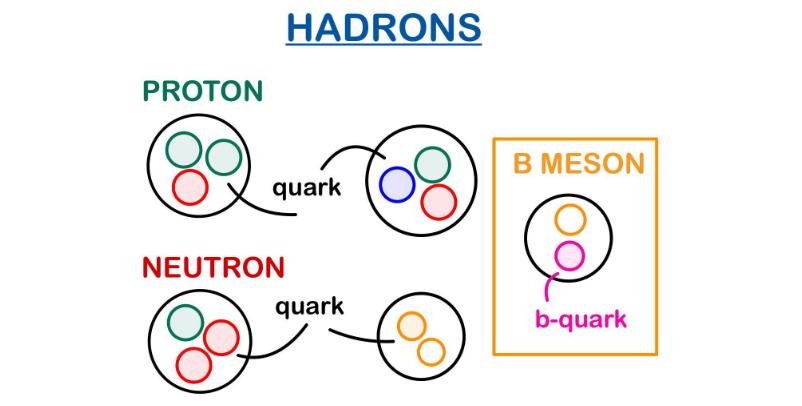

Particle physics is the study of the tiniest elements in the whole Universe. Most of the subatomic particles gather together to form composite objects: some of these form the ordinary matter that we see and touch every day. A very important family of elementary particles is populated by the so-called quarks. The force that governs their interactions is known as strong force and it is described by a theory called QCD (Quantum Chromodynamics). There are in total six quarks, which can bind together to form heavier particles called hadrons.

You’ve surely met the most famous among them: protons and neutrons, which are the constituents of all the objects that surround us. A whole collection of hadrons exists, such that physicists used to refer to it as a “Particle Zoo”. Almost all of them, though, live for a small fraction of a second before decaying into different lighter particles. The study and understanding of these disintegrations is an essential key to building a mathematical description of the particle world.

The Standard Model

Our current formulation is known as Standard Model and it encodes information about all the known elementary particles. In the past decades, it allowed us to predict a wide variety of new particles and explain their behaviours and interactions.

While this model has proven to be extremely successful in explaining a huge range of phenomena, physicists are well aware that it’s not the end of the story. For instance, experiments recently started to show some hints of deviation from the model, especially in processes involving hadrons containing the so-called bottom quark (or $b$ quark). To tell you the truth, we don’t yet understand the source of these discrepancies: that’s why we call them anomalies.

Theory vs Experiments

To further investigate these anomalies we need at least two ingredients: more precise experimental data together with more accurate theoretical predictions.

Experiments

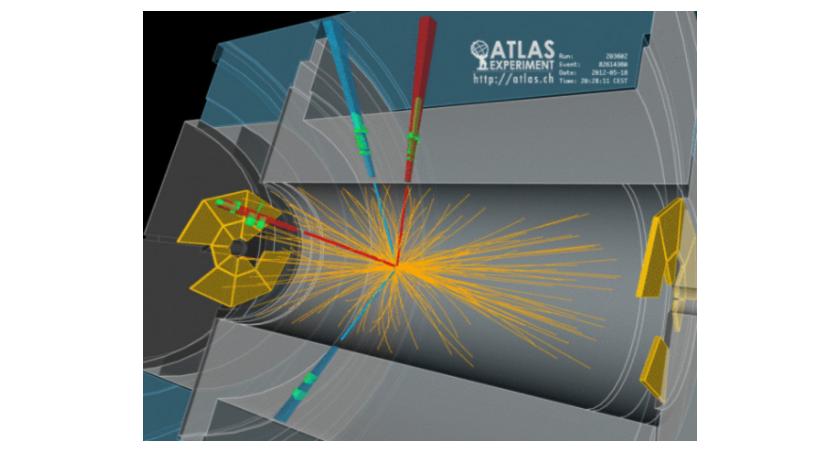

Experiments consist of big colliders, like for example the LHC at CERN in Geneva. In this machine, physicists collide particles to study the product of their interactions.

The general steps can be summarised (and simplified) as follow:

- smash proton-proton;

- track the products of collisions with detectors around the collision point;

- measure properties of the detected particles.

Down here is a sketch of a collision at the ATLAS detector, one of the main experiments at the LHC. In yellow, the new particles produced in the collision scatter away from the collision point and are tracked and detected by the cylindrical detector around them.

Theory

On the theory side, we perform calculations of quantity that can be observed in experiments.

A typical example is the decay rate, which tells us how often given particles

can decay under certain conditions.

Some of these computations are very hard to

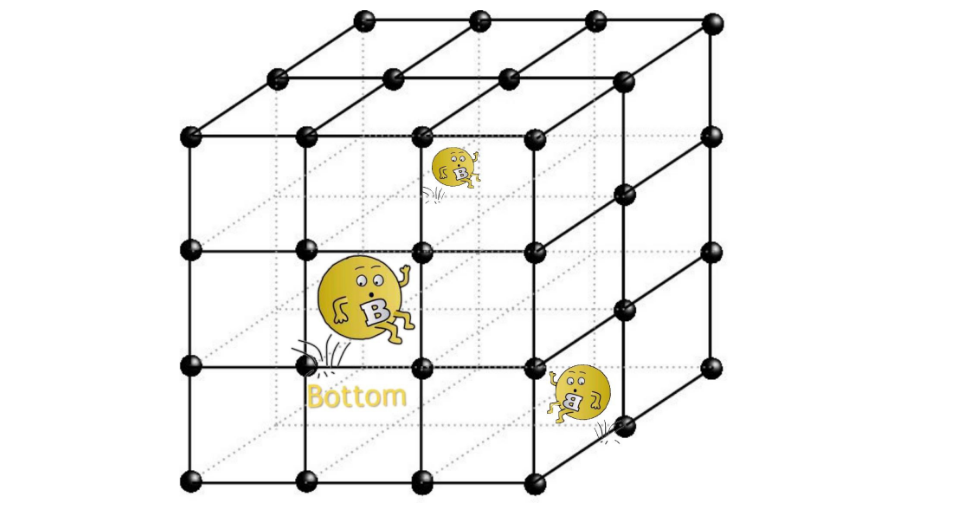

solve with pen and paper: the only possibility is to rely on numerical simulations with the help of supercomputers.

Starting from the pure theoretical model, we translate the mathematical equations into a code that a computer can handle and digest.

For example, instead of dealing with a continuous and infinite space, we pretend that our particles live in a finite cubic lattice,

where they can jump from one site to the other. This formulation of quark interactions

is called Lattice QCD.

A challenging aspect of these tasks is the accuracy of the final results. In order to get predictions as precise as possible these computations need to be iterated many times, such that our codes can easily run for weeks!

My PhD project

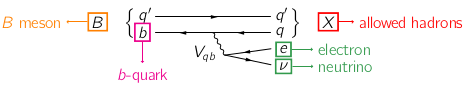

In my project, I focus on performing precise theoretical calculations of decays of a set of hadrons called $B$ meson through Lattice QCD techniques.

This family of particles is extremely important as it contains the $b$ quark, which is the one showing the anomalies mentioned above: indeed, these are usually referred to as $b$ anomalies. Schematically (with what we call Feynman diagram), the decay looks like this:

$V_{qb}$ is a parameter that controls the interaction between the quark b and the generic quark q: this is the quantity that is currently showing discrepancies and the final target of the computations.

Conclusions

The final calculation will represent the first result from Lattice QCD and may be able to shed some light on the $b$ quark anomalies on the $V_{qb}$ parameter: if this discrepancy were to be confirmed, it could lead the path to extend the Standard Model of particle physics and our understanding of the Universe.